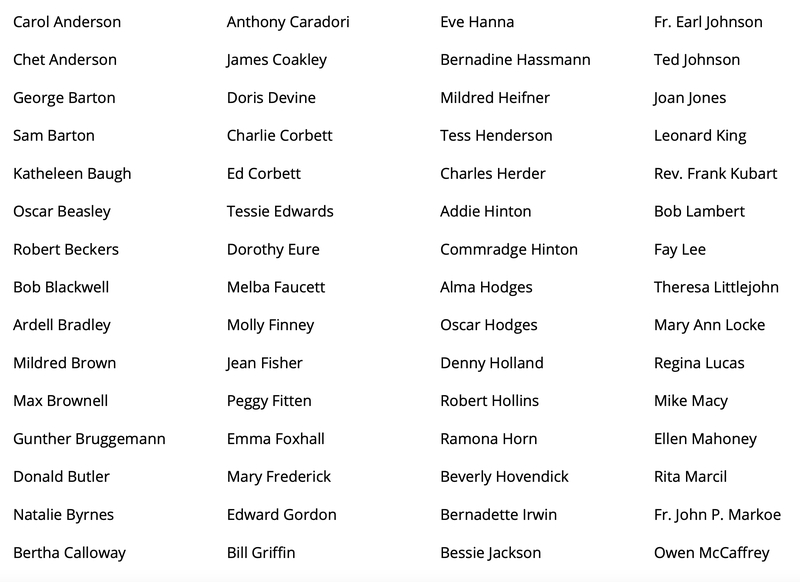

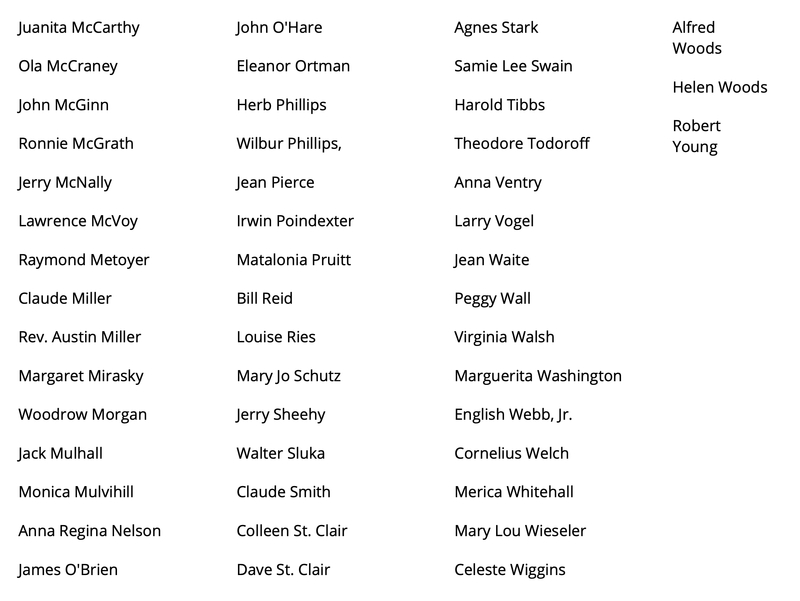

Members

Omaha DePorres Club Active or Associated Members

Mentioned in Meeting Minutes between 1947 and 1960

The DePorres Club attracted members from the Omaha community as well as from among the students and faculty at Creighton University. For many, participation in the DePorres Club was just the start of a lifetime of dedication to advocacy and education.

"I really didn't have time for this but I just couldn't help but be a part of that admirable group of people..."

-- DePorres Club Member Agnes Stark (Wichita), quoted in Holland (2014), 143

Born in a small town in Kansas in 1926, Denny Holland grew up as one of only a handful of local Catholics who sometimes attracted the attention of the local branch of the KKK. In 1944, Holland joined the Navy to train as a fighter pilot as soon as he graduated from high school. Still in training when World War II ended, Holland returned home and decided to use his G.I. Bill benefits to attend Creighton University. Before arriving in Omaha, Denny Holland attended a wedding in place of his brother that was held at the Friendship House in Chicago (Holland 2014). His experience there gave him a new perspective on racial injustice in the United States and imbued him with the desire to do something about it. At Creighton, Holland introduced himself to the recently arrived Fr. John Markoe, who was already notable for his work on behalf of racial justice and, in 1947, the two together began the DePorres Club. Throughout the duration of the Club’s years of activity, Holland served as the president, pouring himself into the work, often at the expense of either solid employment or housing. Even after the Club largely dissolved, Holland remained interested and involved in advocacy in the Omaha community for the remainder of his life.

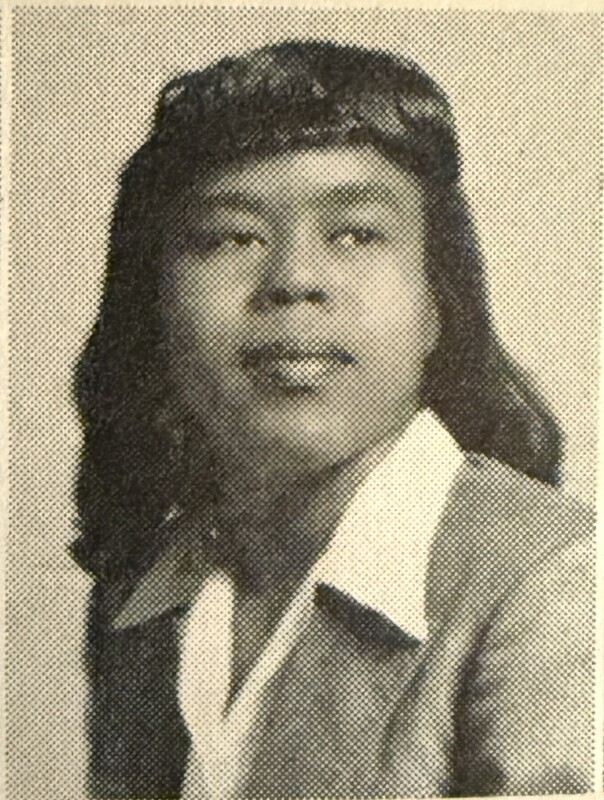

Born in 1927, Tessie Edwards grew up in North Omaha was an early member of the DePorres Club. After graduating from Omaha Central High in 1945, she attended Creighton University (Holland 97). Fr. John Markoe was instrumental in her conversion to Catholicism during her sophomore year at Creighton. An active member of the DePorres Club, she served as corresponding secretary, organized speakers and events, and was appointed a member of the Omaha Consumer’s Mobilization for Fair Employment. She worked with numerous businesses in Omaha such as Evans Laundry, Safeway grocery stores, 7-Up, and Coca-Cola Co. In 1958, after her time in the DePorres Club, Edwards became the first Black teacher in Omaha Catholic Schools. She worked as a teacher for 46 years and maintained a number of commitmnets in civic organizations in Omaha throughout her life. For her lifetime of leadership and advocacy, Edwards received Nebraska Governor’s First Lady’s Outstanding Community Service Award and Creighton gave Edwards the degree of Doctor of Humane Letters, honoris causa. In 2014, the Diocese of Omaha renamed Black Student Catholic Scholarship Fund the Ms. Tessie O. Edwards Memorial Scholarship. She died in 2012 aged 85.

Born in Denver in 1925, Bertha Calloway moved to Omaha by the late 1940s and joined the DePorres Club early on as a student at Creighton. She participated and even took the lead in many of the Club’s notable activities, including the Dixon’s Top Hat Sit In and as a member of the first group of club members to visit the Omaha & Council Bluffs Street Railway Company about their discriminatory hiring practices. Calloway devoted her life to the preservation of Black history and became one of the most importnant and influential advocates for this history in Omaha and nationally. She created the Negro History Society in 1962 and established the Great Plains Black History Museum in North Omaha in 1976.

George Barton, a young Black man and member of the DePorres Club, was wrongly arrested and abused by the Omaha Police Department in late 1956. Following his bail, which was provided by Father Markoe, George sued the OPD for false arrest, aided by his lawyer, Warren Schrempp. The OPD swayed the jury and won their favor on the argument that ‘unless the police actively repressed the North Side, all the rest of Omaha was in danger from the people there.’ Following this verdict, however, Schrempp later appealed the case in 1959 and won for wrongful incarceration. Years later, George’s wife, Beth Schrempp, carried on her late husband’s memory by funding the George Barton Memorial Award, which was offered to students at Creighton Law School.