Coca-Cola Boycott

In the late 1940s, PepsiCo adopted an anti-discrimination hiring policy as part of a nationwide initiative aimed at attracting a larger Black customer base. However, Pepsi's rival, Coca-Cola, did not change its discriminatory hiring practices. In summer 1950, a group of North Omaha businesses stopped carrying Coke products to protest the Omaha Coca-Cola Bottling Company's refusal to hire Black workers. By September, Coca-Cola issued a press release stating that they had agreed to hire four Black workers.

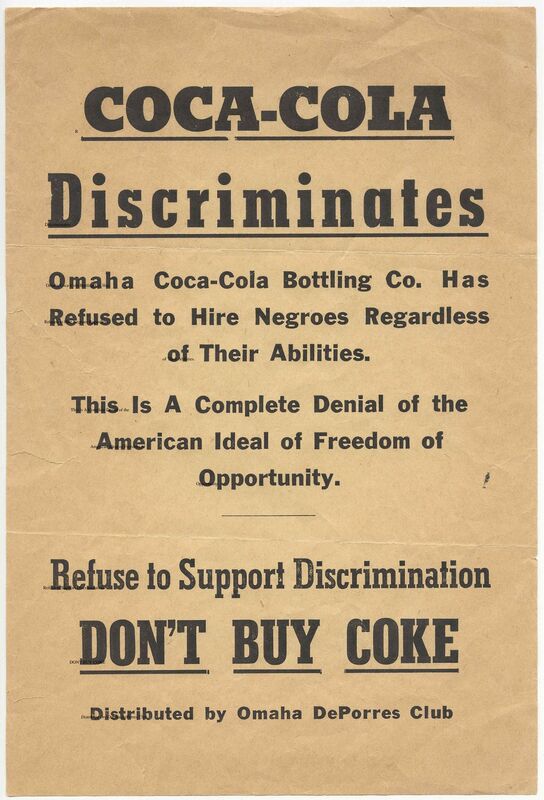

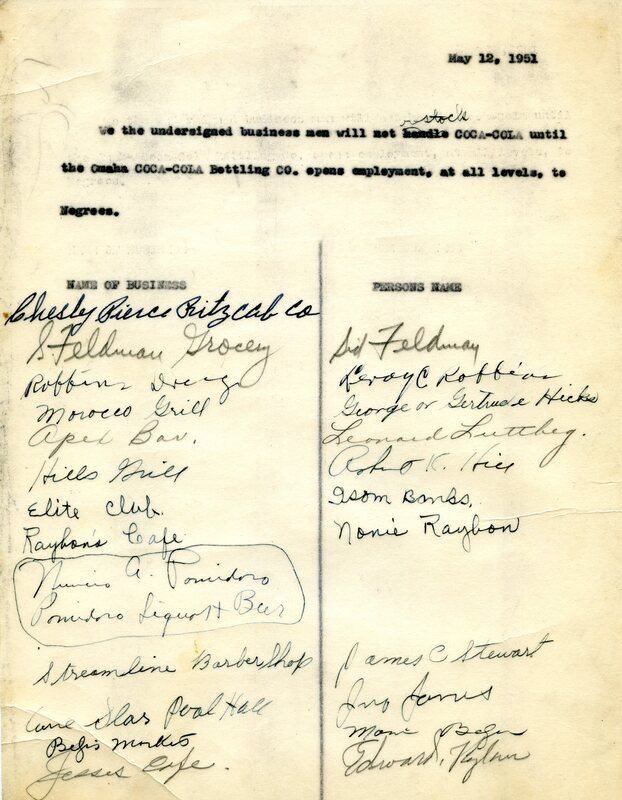

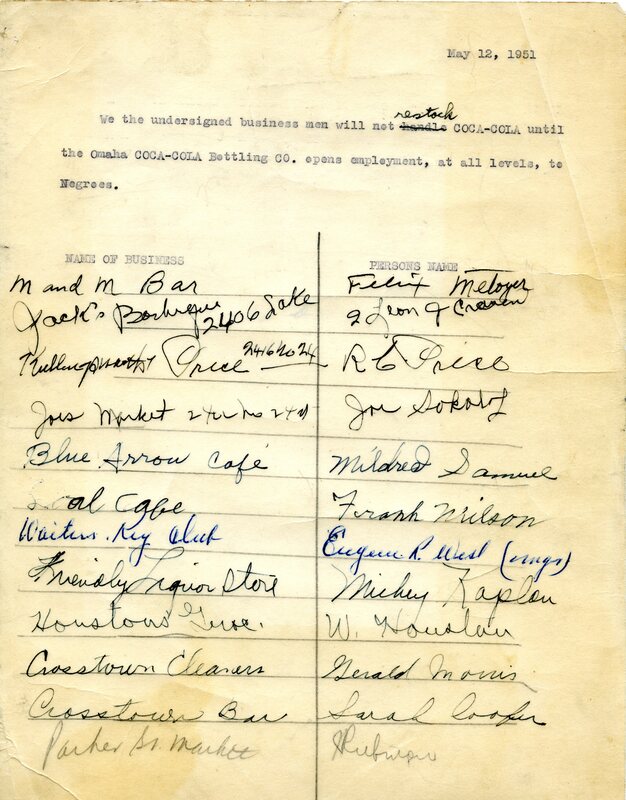

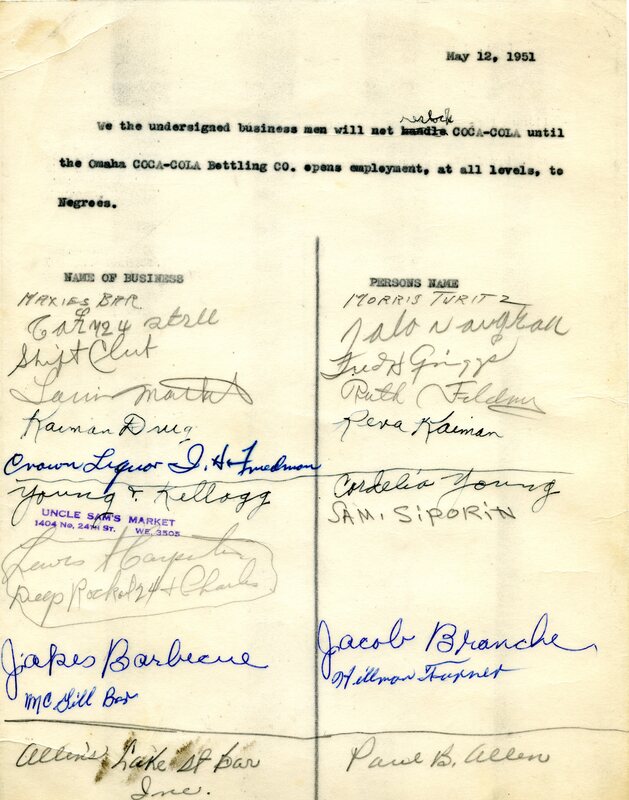

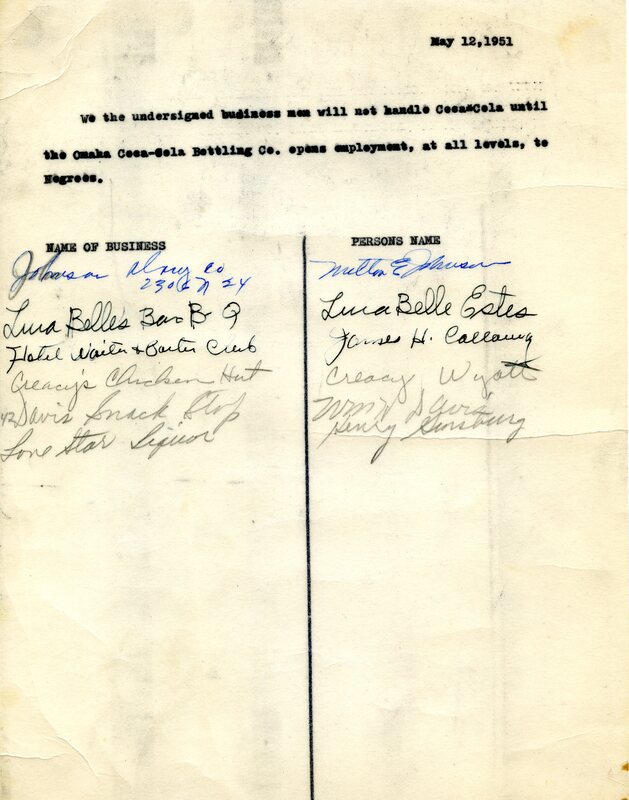

By May 1, 1951, after hearing a series of delays and excuses about hiring Black employees from the Omaha Coca-Cola plant, the DePorres Club launched a boycott against the company. They mailed a letter to Mac Gothard, the manager of the Omaha bottling plant, requesting equal employment policies; otherwise, the boycott would continue. Once again, Gothard assured the DePorres Club that Black workers would be hired, but no action was taken. Throughout May, the Club and other volunteers began picketing in front of the plant and distributing over 10,000 "Don't Buy Coke" leaflets throughout the North Omaha area. Father Markoe and Denny Holland initiated a petition that garnered 43 signatures from local businesses, contingent upon their agreement to refrain from restocking Coca-Cola products until the company adopted fair employment practices.

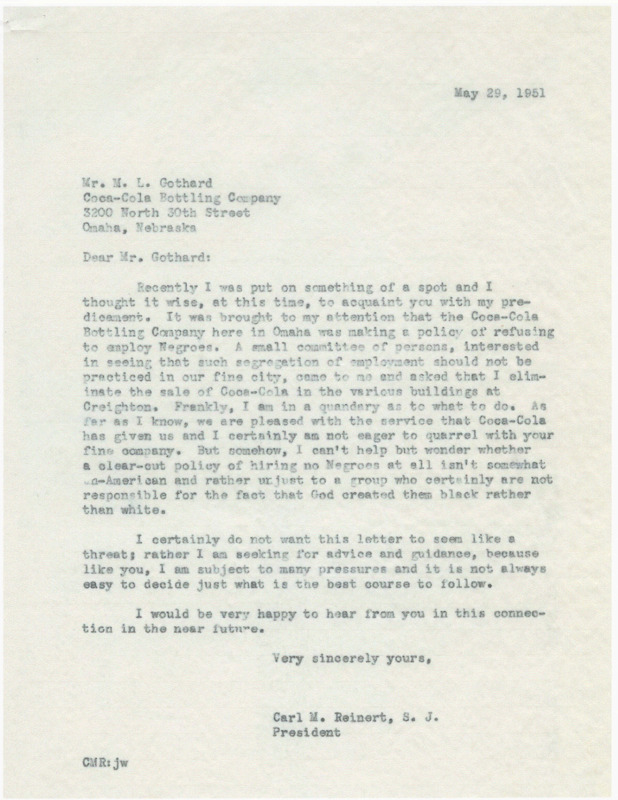

By the end of May, it seemed that the boycott was successful -- the Omaha Urban League reported that Gothard would hire two Black workers for semi-skilled labor at $50 per week. The Club was hesitant about this announcement, opting to wait until they had seen concrete evidence that Black workers were hired. Instead of sending a congratulatory letter, Fr. Carl Reinert, president of Creighton University, wrote to Coca-Cola stating that the university was considering stopping the sale of its products on campus:

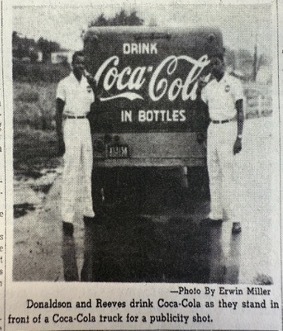

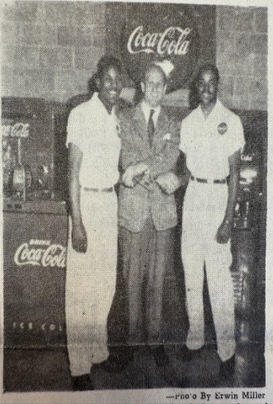

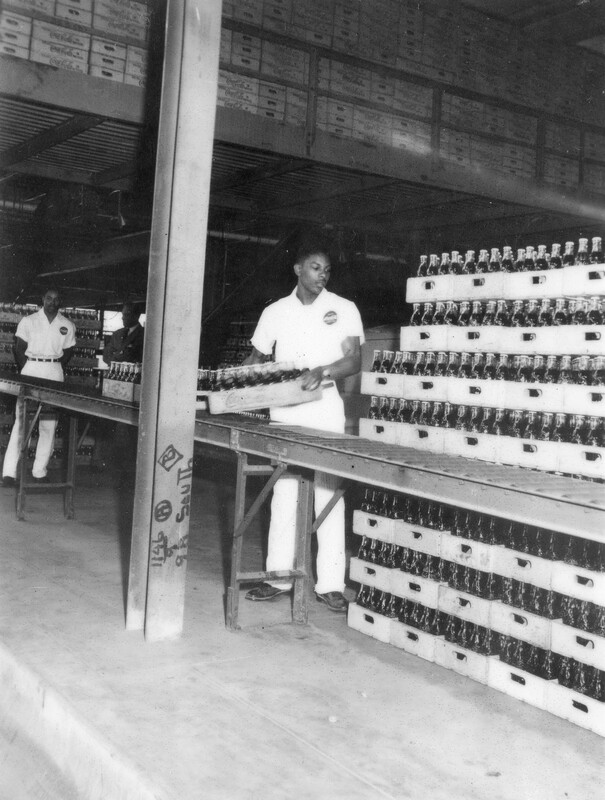

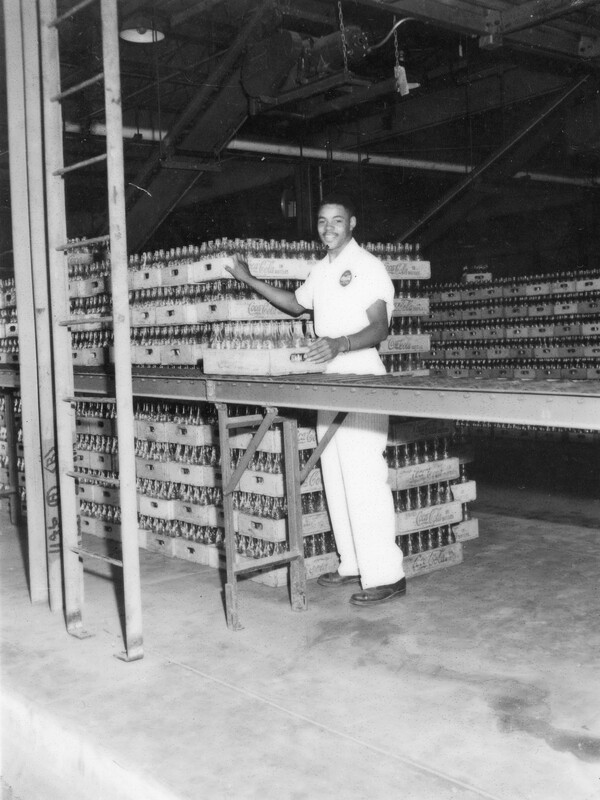

Gothard wrote back, stating that the company had just hired two Black workers and insisting that the DePorres Club's actions did not influence the decision. However, it turns out that the Coca-Cola Bottling Company and one of the local newspapers, Omaha Guide, had staged a photoshoot with two Black men posing as newly hired workers. The photographer, Erwin Miller, was initially unaware that the photoshoot was staged, but upon learning it, he sent the negatives to Holland and refused to give them to the Omaha Guide. Further invigorated by this discovery of Coca-Cola's deception, the DePorres Club continued the boycott.

On June 12, at a meeting with representatives from DePorres Club, the Urban League, and the Coca-Cola Bottling Company, Gothard announced that the company had changed its hiring policy. Employment at the plant was now open to all, regardless of race, and two Black employees were hired. In facing off against one of their biggest opponents yet, the DePorres Club achieved its most significant victory to date, making substantial progress in the small confines of North Omaha.

For more information, see Holland (2014), Chapters 15, 16, 17.