Diocesan

History of St. Benedict the Moor Parish

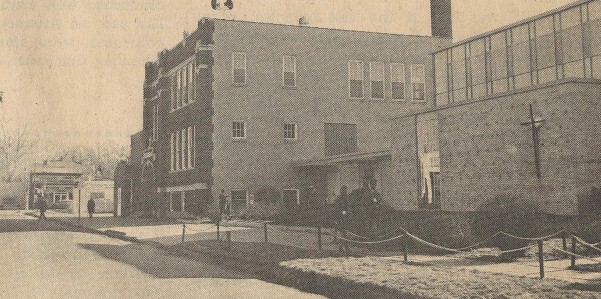

St. Benedict the Moor Parish was founded as a mission in 1919 by Fr. Francis, S.J. to minister to the Black Catholics on the Near North Side of Omaha who had been denied admittance to other churches (Sasse 2017). From 1923-1968, St. Benedict's also operated a parish school. Though the designation as a mission was necessary in order to serve the entirety of Omaha's Black population, pastors at other churches used it as an excuse to bar Black parishioners from their parishes. An article in the November 21, 1952 issue of the Omaha Star, entitled, "St. Benedicts, Promoter of Racial Segregation," pointed out that the existence of an "unbounded Negro Catholic Church" in an act of de facto segregation made the city's remaining parishes "White Catholic churches" (Markoe Papers, B4 F27).

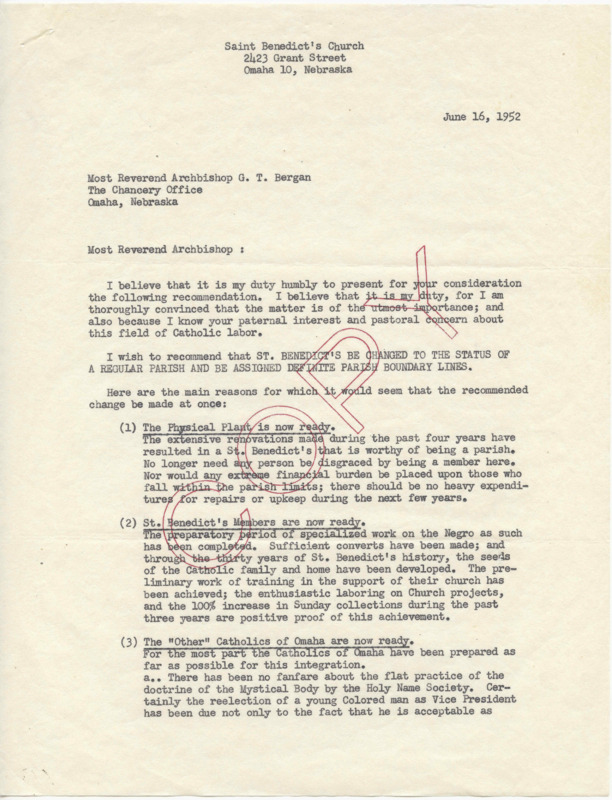

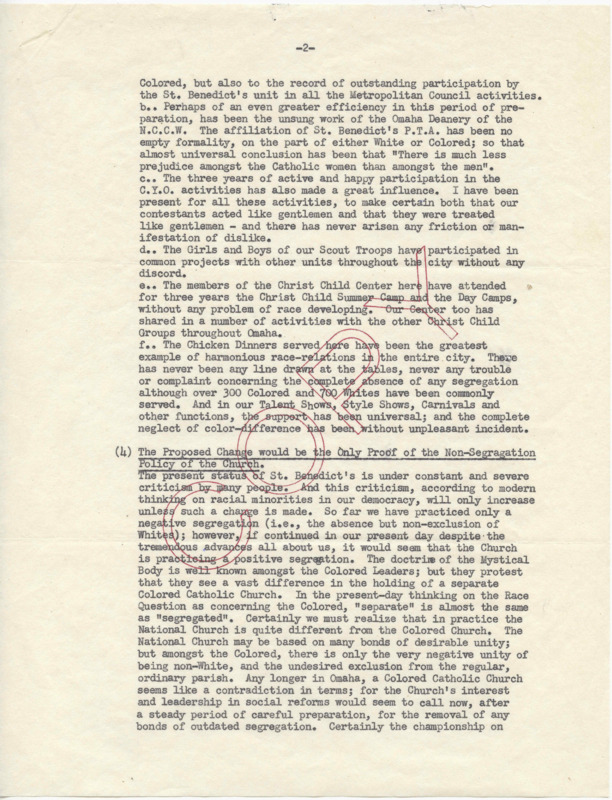

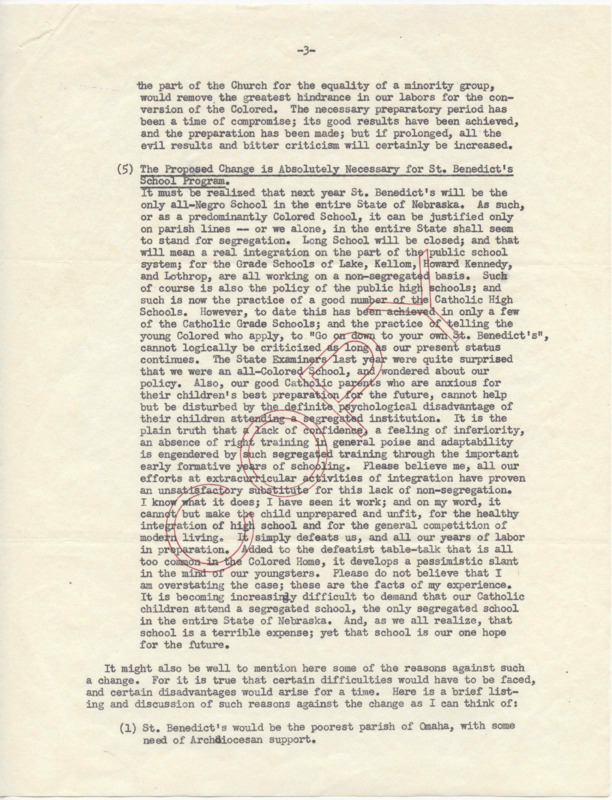

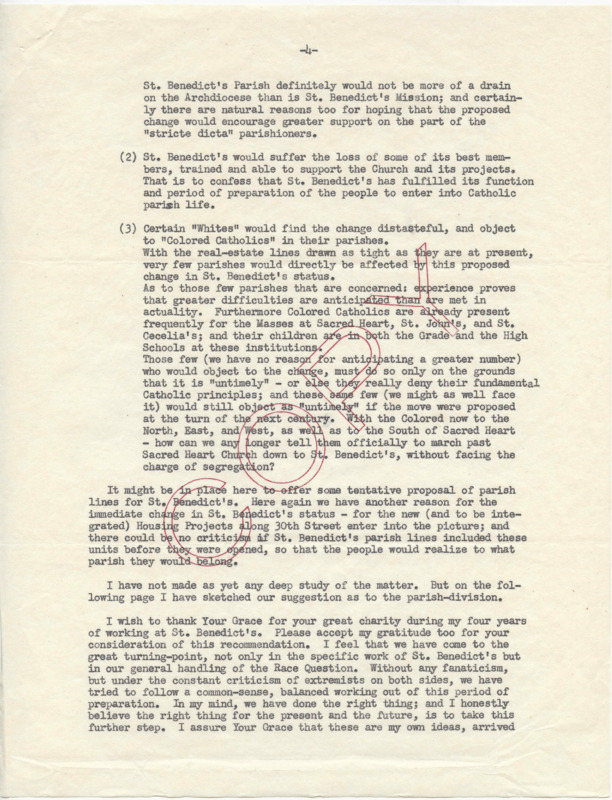

Unbeknownst to the public, Fr. Killoren of St. Benedict's had submitted a recommendation to Archbishop Bergan that it be designated a "regular" parish and "assigned definite parish boundary lines" (Markoe Papers, B4 F27). He sent the recommendation on June 16, 1952, five months before the Omaha Star article was published. He believed that the parish's missionary work had been completed and it would function best as a regular parish going forward. While he acknowledged that some of the white parishioners in Omaha might protest he said:

"Those few (we have no reason for anticipating a greater number) who would object to the change, must do so only on the ground that it is 'untimely'— or they really deny their fundamental Catholic principles; and these same few (we might as well face it) would still object as 'untimely' if the move were proposed at the turn of the next century" (Markoe Papers, B4 F27).

Archbishop Bergan agreed that the time had come to assign St. Benedict's official parish boundaries and discontinue its mission designation. That transition happened in 1953.

The de facto segregation of Omaha parishes did not disappear. A document dated October 24, 1967, entitled "Catholics Ask for Change" detailed similar issues with St. Benedict's. It expressed a frustration with the diocese and donors throwing money at St. Benedict's without trying to change the institutionalized white supremacy within the Church.

"'Real meaningful leadership—not sponsorship—was denied us. The problem has reached a point where no amount of money can change the image of the Church in this area without first changing the Church's attitude. St Benedict's is viewed as the Black Vatican. They tell us to 'use it, be happy, and thankful and we will keep adding to it

'To change this image the Catholic Church, with all its resources, must embark on an effort to help the oppressed people of this area to gain full equality. Not because we are Negro people or poor people, but because we are God's people.'" (Markoe Papers, B4 F27).

Archbishop Bergan

Archbishop Bergan was appointed head of the Archdiocese of Omaha on February 7, 1948. From the beginning of his leadership, Archbishop Bergan was sympathetic to the civil rights struggle, saying in August 1948 that he “wouldn’t stand for segregation on the basis of color.” Despite his belief that racism was wrong, the Archbishop was slow to action not encouraging radical change within the diocese. In August 1953, Archbishop Bergan spoke at a rally hosted by the Holy Name Society and stated publicly that a person is not a true Catholic unless they work to right the wrongs of racial injustice. As he rallied the crowd, the Archbishop asked, “Are we followers of Christ who loved all men and died for all without exception?” (Markoe Archives B7, F22) The Archbishop then took his words into action, founding a social action department within the diocese and calling for open advocacy and fair housing practices.

“Are we followers of Christ Who loved all men and died for all without exception? Are we the first-class citizens while all others must stand at a safe distance in the rear?” “I ask you Holy Name men to be sincere. You should favor and work for sound, honest, proper legislation to remedy this crying evil. We are not Catholics unless we do. We are not only putting into practice the teachings of Christ and his Church, but we are delaying the influence of democracy around the world”

Sacred Heart Parish and Monsignor Ostdick

Monsignor Ostdick

Monsignor Ostdick was the pastor of Sacred Heart Parish while the DePorres Club was active. Due to its proximity to North Omaha, Monsignor Ostdick had to determine whether or not he would allow Black individuals to attend the parish and school. Denny Holland first spoke with Ostdick in November of 1946. When Holland stated, “then Father you will not accept Negros in your parish,” Msgr. Osdick responded, “I rather you not state it that way. They have a parish, but not here” (Markoe Archives B3 F23). Ostdick claimed his hostility was because he did not want to offend Fr. Moreland, pastor of St. Benedict’s. The conversation between Denny Holland and Msgr. Ostdick continued in 1957 when Denny sent Ostdick some literature on racial justice. In his response, Msgr. Ostdick claimed that he had always supported civil rights, saying, “I have been fired on many times from both sides and have received no comfort and encouragement from anyone no matter how hard I sacrificed myself and tried to please all” (Markoe Archives B4 F20). Although statements from Msgr. Ostdick showed that he became more sympathetic to the Civil Rights movement over time, he was unwilling to admit he was at one point part of the problem.

St. Benedict's Vs Sacred Heart

St. Benedict the Moor and Sacred Heart Parishes have had an intertwined history since the mid-1900s. Historically, St. Benedict's had been an Black parish, whereas Sacred Heart was predominantly white. As North Omaha became more segregated due to redlining, Black families began attending Sacred Heart and attempting to enroll their children at the parish school. This caused white parishioners to move out of the parish area, movement similar to that in many other cities across the nation (McGreevy, 1998). The DePorres Club attempted to bridge the gap between the two parishes, but after interviewing Sacred Heart leadership in 1946, the Club received pushback about attempts to integrate the communities (Markoe Archives B3 F23). Seventy-five years later, the parishes are both members of the Historic 24th Street Family of Parishes and share a pastor (The Historic 24th Street Family of Parishes).