Jesuit

Jesuits in the United States: Slavery and Jim Crow

Jesuits participated in the egregious institution of slavery in America. Through their involuntary labor, slaves “helped establish, expand, and sustain Jesuit missionary efforts and educational institutions” in America (Slavery, History, Memory, and Reconciliation). For example, Georgetown University owes its continued existence and prestige to the now infamous 1838 sale of 272 enslaved people. In addition, St. Stanislaus Seminary, the site of Fr. John Markoe’s spiritual formation, was the product of slave labor. Jesuit slaveholding was so pervasive that it is a legacy “shared by all Jesuits and Jesuit institutions” (Slavery, History, Memory, and Reconciliation).

As missionaries, Jesuits prioritized the eventual eternal salvation of enslaved people over their worldly experiences of injustice (Schmidt and Critchley-Menor, 2020). Jesuits dutifully evangelized but, like most Catholic missionaries of the era, they most often stressed the conversion aspect of missionary work and neglected their duty to demonstrate Catholic values through their actions. Stripped of their autonomy, slaves were manipulated and abused by the very people who had assumed ministry of their spiritual wellbeing.

The Jesuit attitude toward Black Catholics “as objects of ministry rather than agents of their own faith” proved resolute against the forces of emancipation and Reconstruction (Schmidt and Critchley-Menor, 2020). This practice of objectification thrived in the Jim Crow era. Jesuit schools exclusively educated white students. Administrators feared the financial repercussions of integration and opted to prioritize wealthy donors’ happiness over the social advancement of potential Black students. By prohibiting Black students, they fortified both legislated and de facto segregation. Though their discriminatory practices were never codified, American Jesuits excluded Black men from the order as well. Black candidates were deemed unfit for religious life as they would not prove “useful” to the order. This evaluation was rooted in the notion that Black priests could not have any authority over white Catholics. (Schmidt and Critchley-Menor, 2020). Such prejudice was so ubiquitous among American Jesuits that it even permeated the rare efforts to further racial equality.

Jesuit Outliers: Civil Rights Activists

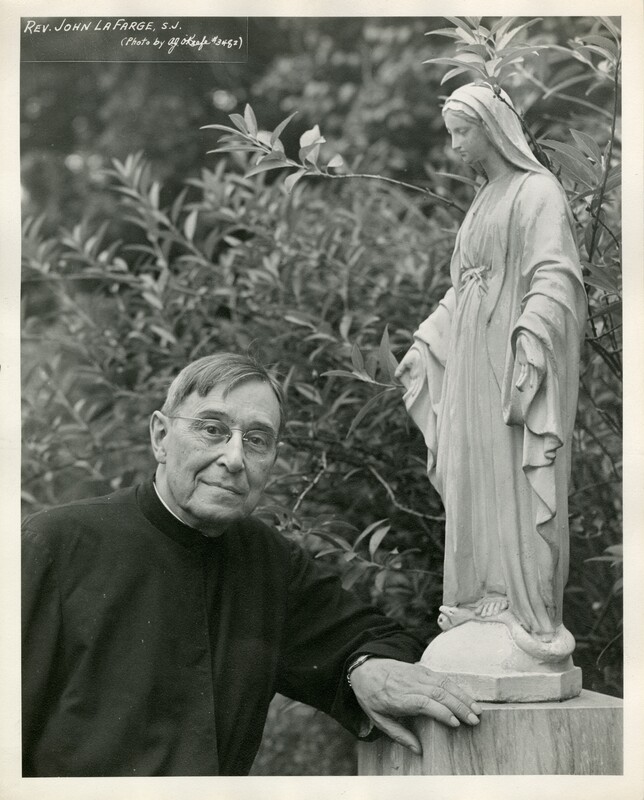

John LaFarge, SJ (1880-1963)

Ideals:

- natural law

- interracialism

- gradualism

- anti-communism

- education as the solution to racism

- value of minority groups to the greater community

John LaFarge, SJ was the most prominent Jesuit voice in the Civil Rights Movement. At the core of his work was the belief that “racism was the result of ignorance rather than, for instance, the result of adherence to dogmas of racial inferiority. He accordingly advocated a gradualist response to the race problem that focused on education” (Chamedes, 2013). LaFarge spent the majority of his priestly career educating Catholics through his writing as an editor at America, a Jesuit magazine published in New York. He established the Catholic Interracial Council of New York in 1934.

LaFarge published his most influential book, Interracial Justice: A Study of the Catholic Doctrine of Race Relations, in 1937. Much of his interracial theory was inspired by his assignment as a young Jesuit to St. Mary’s County in southern Maryland. The Jesuit missions in that region dated back to the 1600s and many of the impoverished Black Americans that La Farge ministered to were the descendants of slaves who had worked in the area (Keane and McDermott, 2008). This work taught him that any lack of “intellectual or economic achievements” by Black Americans actually stemmed from the “economic and cultural impoverishment” that Black Americans “had suffered at the hands of the ruling classes” since their arrival to the continent (Keane and McDermott, 2008). Invoking a Thomistic understanding of natural law, LaFarge asserted that “the rights of individuals were not bestowed by governments, but were merely protected by them” (Keane and McDermott, 2008). Pope Pius XI, impressed by LaFarge’s writing, asked him to collaborate on an encyclical entitled “The Dignity of the Human Race.”

LaFarge was instrumental in the early push for interracial justice among Catholics. Though his influence in the civil rights movement had dwindled by the 1960s, his status as a pioneer of Catholic interracialism earned him a spot on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial during Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech (Keane, 2023). LaFarge recognized the importance of the moment, saying, “The Aug. 28 March was but a beginning, a summons to unceasing effort. The hour is bound to come—and the less delay the better—when North and South alike will set a final seal upon its simple goal of jobs and freedom for all citizens—yes for all” (LaFarge, 1963).

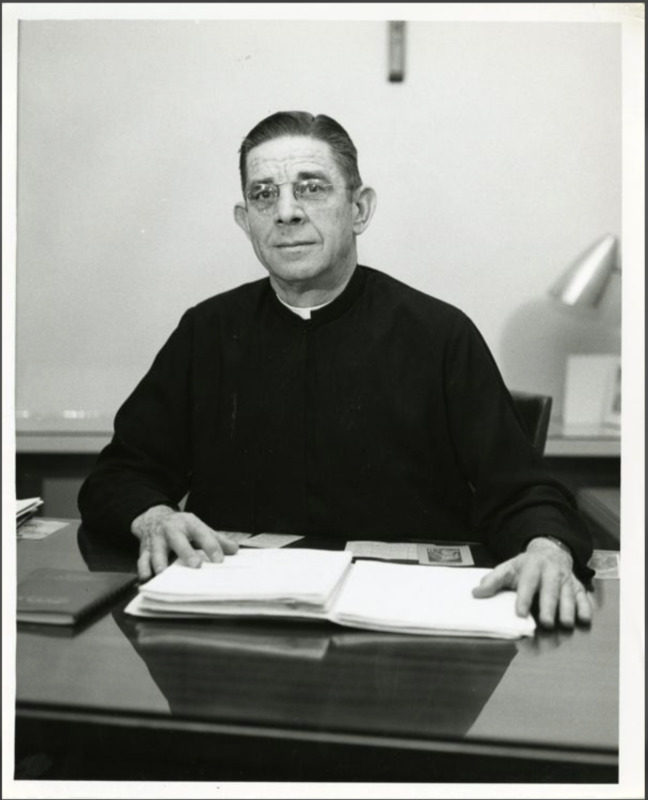

Louis J. Twomey, SJ (1905-1969)

Ideals:

- human dignity according to Catholic Social Teaching

- labor rights

- interracialism

- anti-communism

Louis J. Twomey, S.J. approached racial justice from a labor rights standpoint. His childhood in Tampa, FL instilled a strong prejudice against Black Americans and an admiration for the Confederacy, but his devotion to labor rights challenged these beliefs (Goldstein, 2024). Twomey studied at St. Louis University’s Institute of Social Order, which stressed interracialism. There, Twomey realized that Catholic Social Teaching demanded solidarity with Black Americans (Goldstein, 2024).

Twomey founded the Institute of Industrial Relations at Loyola University New Orleans. He established himself as a labor activist, and he used this renown to combat racism within the labor rights movement. He stressed that “concern for working people necessitated concern for racial equality” (Goldstein, 2024). He also argued that “White supremacy, in presenting the United States to the world as a land of inequality, only served to fuel communism’s spread” (Goldstein 2024). Under Twomey’s direction, the institute began publication of its social-justice newsletter, Christ’s Blueprint for the South. Twomey intended the newsletter for an exclusively Jesuit audience. It was “a medium for Jesuits to discuss privately how best to implement the social teachings of the church” (Goldstein, 2024). Counted among the few non-Jesuit readers of the newsletter was Twomey’s friend and ally, Martin Luther King, Jr.

Jesuits as the Great Stumbling Block

In his 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Martin Luther King, Jr. described white moderates as “the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom” (King, 1963). In King’s estimation, white moderates–people of general good will who did not oppose the struggle of Black Americans for civil rights but instead remained apathetic to it or inactive in it–presented a greater obstacle on the road toward racial equality than members of the Ku Klux Klan. Unfortunately, the majority of American Jesuits during the early civil rights era, particularly those in positions of power, fell into this troublesome category (Homan, 2020). It is this environment in which John Markoe worked for change.

“As Jesuits have sought people to fix . . . we have sought a half justice, one that begins to improve lives but never taking a step far enough to vacate our own authority and comfort. We fear reprisal. We maintain order. We are moderate” (Homan, 2020).

As white moderates, the Jesuits prioritized order over justice. Pastors of local churches and administrators of large universities alike feared integration would ignite a period of white flight and divestment (Homan, 2020). They did not want to offend white Catholics and disrupt the status quo. Most American Jesuits recoiled from direct action because it highlighted the underlying tension festering beneath the facade of a pleasant society. As white men, Jesuits could ignore the tension that consumed Black Catholics’ every waking hour. They “remained silent behind the anesthetizing security of stained glass windows” (King, 1963).

If some Jesuits expressed any support for the pursuit of racial equality, other Jesuits quickly followed that with a reminder to be patient. They fit King’s white moderate mold by “paternalistically” setting “the timetable for another man’s freedom” (King, 1963). In urging patience, Jesuits divulged their belief that change was inevitable. But without action, “time itself becomes an ally of the forces of social stagnation” (King, 1963).

Those Jesuits who chose not to look away and took part in direct action were met with opposition. Seen as civil rights “agitators,” these men were often reassigned by their superiors to less influential positions in locations farther North. The superiors believed that these new, northern locations presented fewer opportunities for activism on behalf of Black Catholics. They did not consider the fact that the Catholic Church was segregated throughout the United States, not just in the South.

Following his outspoken support for the integration of Saint Louis University in southern Missouri, Fr. Markoe was relocated north to Creighton University in Omaha, NE. That didn’t stop his crusade for interracial justice. “Everyone fights on the battlefield he’s allotted, and for Father John Markoe, the arena became Omaha” (Markoe Papers, B4 F25).

Despite the valiant efforts of priests like Fr. Markoe, the predominant Jesuit mindset during the civil rights era is best summed up by their frequent referral to “the Negro problem.” (Homan, 2020). This wording betrayed an utter lack of respect for Black Americans. It portrayed them as a problem to be solved rather than a valuable facet of the United States and the Catholic Church to be fully embraced.

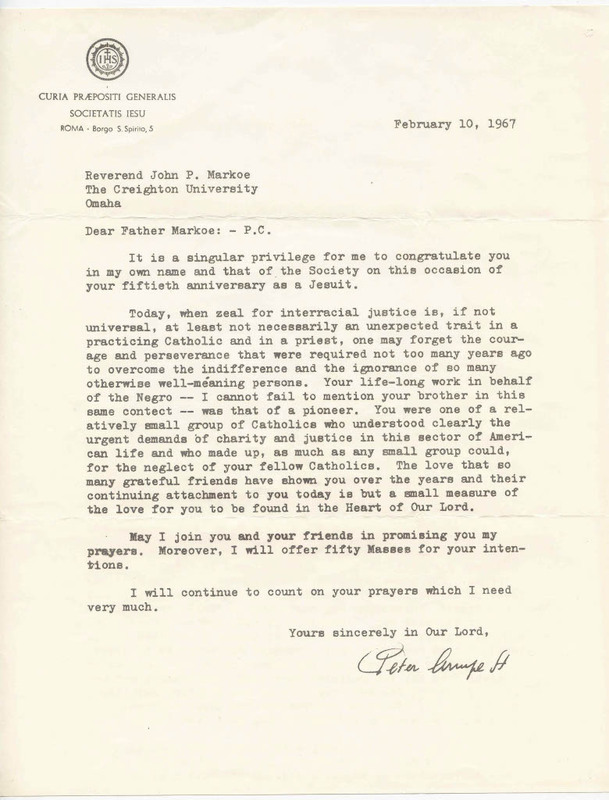

Pedro Arrupe: The Turning Point

The installation of Pedro Arrupe, S.J. as Superior General of the Society of Jesus in 1965 proved to be a turning point for the order. Arrupe was a champion for social justice and solidarity with the poor and marginalized members of society. On February 10, 1967, Arrupe sent Fr. John Markoe a letter of congratulations for his 50th jubilee. He used the occasion to commend Markoe on his pioneering work for interracial justice. Arrupe praised Markoe for the “courage and perseverance” that his early support of civil rights required (Markoe Papers, B2 F1).

“Your life-long work on behalf of the Negro– I cannot fail to mention your brother in this same contect [sic]– was that of a pioneer. You were one of the relatively small group of Catholics who understood clearly the urgent demands of charity and justice in this sector of American life and who made up, as much as any small group could, for the neglect of your fellow Catholics” (Markoe Papers, B2 F1).

Then, in November of 1967, Arrupe sent out a letter entitled, “Interracial Apostolate” to every American Jesuit. In it, Arrupe lamented the fact that Jesuit activism on behalf of Black Americans had, up until that point, been implemented on an individual basis. He mentioned John Markoe by name as one of the “great pioneers” in service to Black Americans. He then issued an institutional call to action.

Acknowledging that racial discrimination had condemned a considerable percentage of Black Americans to a generational cycle of poverty, Arrupe encouraged American Jesuits to leave their white, middle class comfort zone, recommit to the spirit of poverty, and minister to inner city communities. Arrupe would not coin the term “option for the poor” until 1968, but the well-known aspect of modern day Catholic social teaching was evident in his argument for the pursuit of racial justice and charity.

To ensure that his words created concrete change, Arrupe’s letter outlined ten policies ‘indicative of the course which Jesuit thought and action should take in attacking the twin evils of racial injustice and poverty in the United States” (Arrupe, 1967). He directed the American Jesuits to eliminate all forms of racial segregation or discrimination from their ministries, welcome Black parishioners, and foster vocations among Black Catholics. Jesuit high schools, colleges, and universities were to encourage Black student enrollment, establish scholarships and special programs to help disadvantaged Black students meet admission requirements, and recruit Black faculty members. He even stipulated that Jesuit institutions only contract out to businesses with fair employment practices. Finally, Arrupe urged the Jesuits to cooperate with religious and secular organizations making headway in the civil rights movement. Arrupe hoped that these policies would realign Jesuit “manpower and resources to meet the crying needs of our brothers in Christ who languish in racial degradation and inhuman poverty” (Arrupe, 1967).

For more, see Pedro Arrupe's "Interracial Apostolate."