Jesuit Outliers: Civil Rights Activists

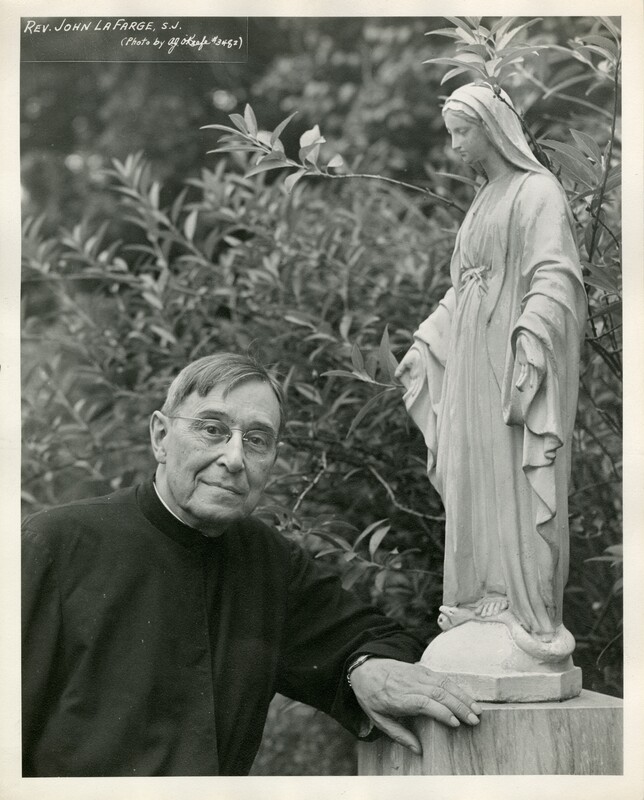

John LaFarge, SJ (1880-1963)

Ideals:

- natural law

- interracialism

- gradualism

- anti-communism

- education as the solution to racism

- value of minority groups to the greater community

John LaFarge, SJ was the most prominent Jesuit voice in the civil rights movement. At the core of his work was the belief that “racism was the result of ignorance rather than, for instance, the result of adherence to dogmas of racial inferiority. He accordingly advocated a gradualist response to the race problem that focused on education” (Chamedes, 2013). LaFarge spent the majority of his priestly career educating Catholics through his writing as an editor at America, a Jesuit magazine published in New York. He established the Catholic Interracial Council of New York in 1934.

LaFarge published his most influential book, Interracial Justice: A Study of the Catholic Doctrine of Race Relations, in 1937. Much of his interracial theory was inspired by his assignment as a young Jesuit to St. Mary’s County in southern Maryland. The Jesuit missions in that region dated back to the 1600s and many of the impoverished Black Americans that La Farge ministered to were the descendants of slaves who had worked in the area (Keane and McDermott, 2008). This work taught him that any lack of “intellectual or economic achievements” by Black Americans actually stemmed from the “economic and cultural impoverishment” that Black Americans “had suffered at the hands of the ruling classes” since their arrival to the continent (Keane and McDermott, 2008). Invoking a Thomistic understanding of natural law, LaFarge asserted that “the rights of individuals were not bestowed by governments, but were merely protected by them” (Keane and McDermott, 2008). Pope Pius XI, impressed by LaFarge’s writing, asked him to collaborate on an encyclical entitled “The Dignity of the Human Race.”

LaFarge was instrumental in the early push for interracial justice among Catholics. Though his influence in the civil rights movement had dwindled by the 1960s, his status as a pioneer of Catholic interracialism earned him a spot on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial during Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech (Keane, 2023). LaFarge recognized the importance of the moment, saying, “The Aug. 28 March was but a beginning, a summons to unceasing effort. The hour is bound to come—and the less delay the better—when North and South alike will set a final seal upon its simple goal of jobs and freedom for all citizens—yes for all” (LaFarge, 1963).

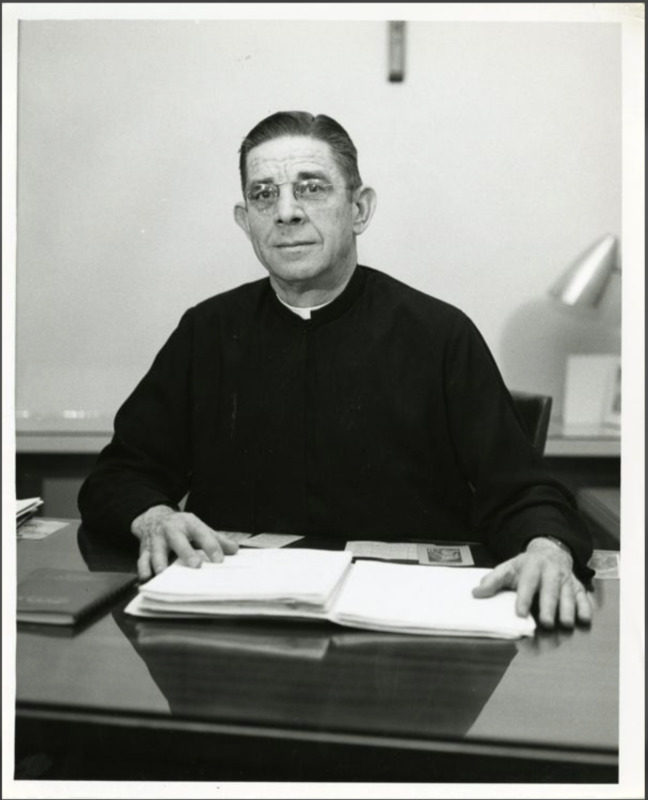

Louis J. Twomey, SJ (1905-1969)

Ideals:

- human dignity according to Catholic Social Teaching

- labor rights

- interracialism

- anti-communism

Louis J. Twomey, S.J. approached racial justice from a labor rights standpoint. His childhood in Tampa, FL instilled a strong prejudice against Black Americans and an admiration for the Confederacy, but his devotion to labor rights challenged these beliefs (Goldstein, 2024). Twomey studied at St. Louis University’s Institute of Social Order, which stressed interracialism. There, Twomey realized that Catholic Social Teaching demanded solidarity with Black Americans (Goldstein, 2024).

Twomey founded the Institute of Industrial Relations at Loyola University New Orleans. He established himself as a labor activist, and he used this renown to combat racism within the labor rights movement. He stressed that “concern for working people necessitated concern for racial equality” (Goldstein, 2024). He also argued that “White supremacy, in presenting the United States to the world as a land of inequality, only served to fuel communism’s spread” (Goldstein 2024). Under Twomey’s direction, the institute began publication of its social-justice newsletter, Christ’s Blueprint for the South. Twomey intended the newsletter for an exclusively Jesuit audience. It was “a medium for Jesuits to discuss privately how best to implement the social teachings of the church” (Goldstein, 2024). Counted among the few non-Jesuit readers of the newsletter was Twomey’s friend and ally, Martin Luther King, Jr.

For more, see Dawn Eden Goldstein's America article, "A little-known Jesuit's battle for racial justice in the Deep South."