Military Service

John Prince Markoe’s life was one of sharp turns — from the military parade grounds of West Point to the classrooms of Jesuit universities, and from the battlefields of the American Southwest to the front lines of social justice. Before arriving at West Point, Markoe’s path had already begun to reflect the promise and contradictions of his era. He attended Webster grade school and later St. Thomas Academy, a Catholic military high school in Saint Paul. These institutions instilled a sense of discipline and service that would guide — and sometimes conflict with — the choices of his early adulthood.

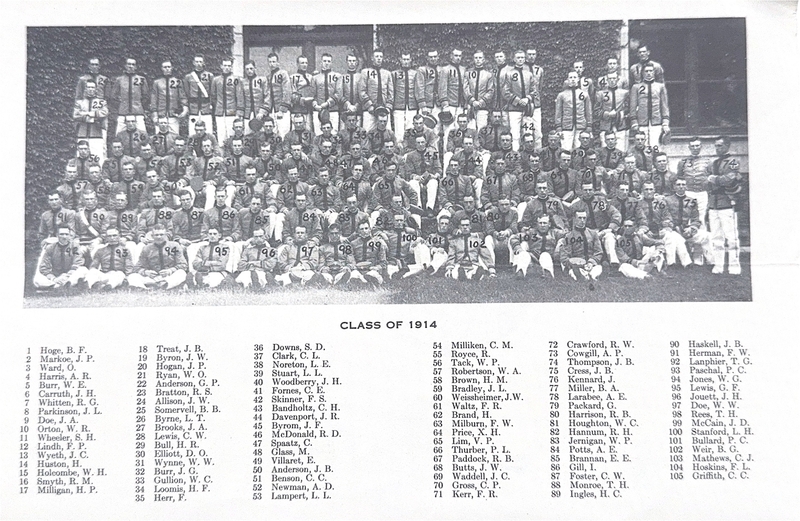

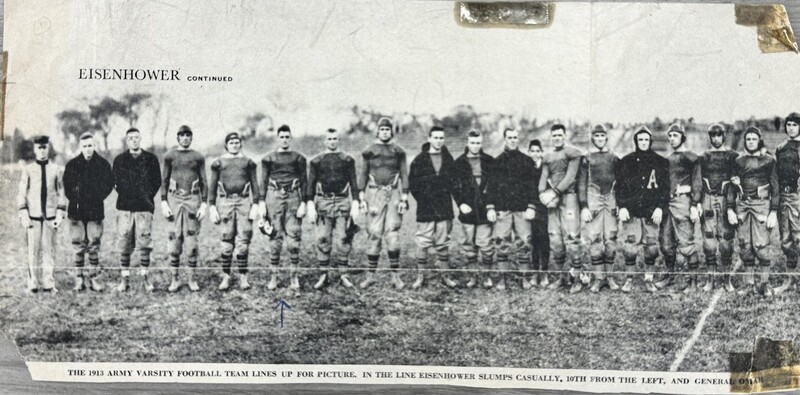

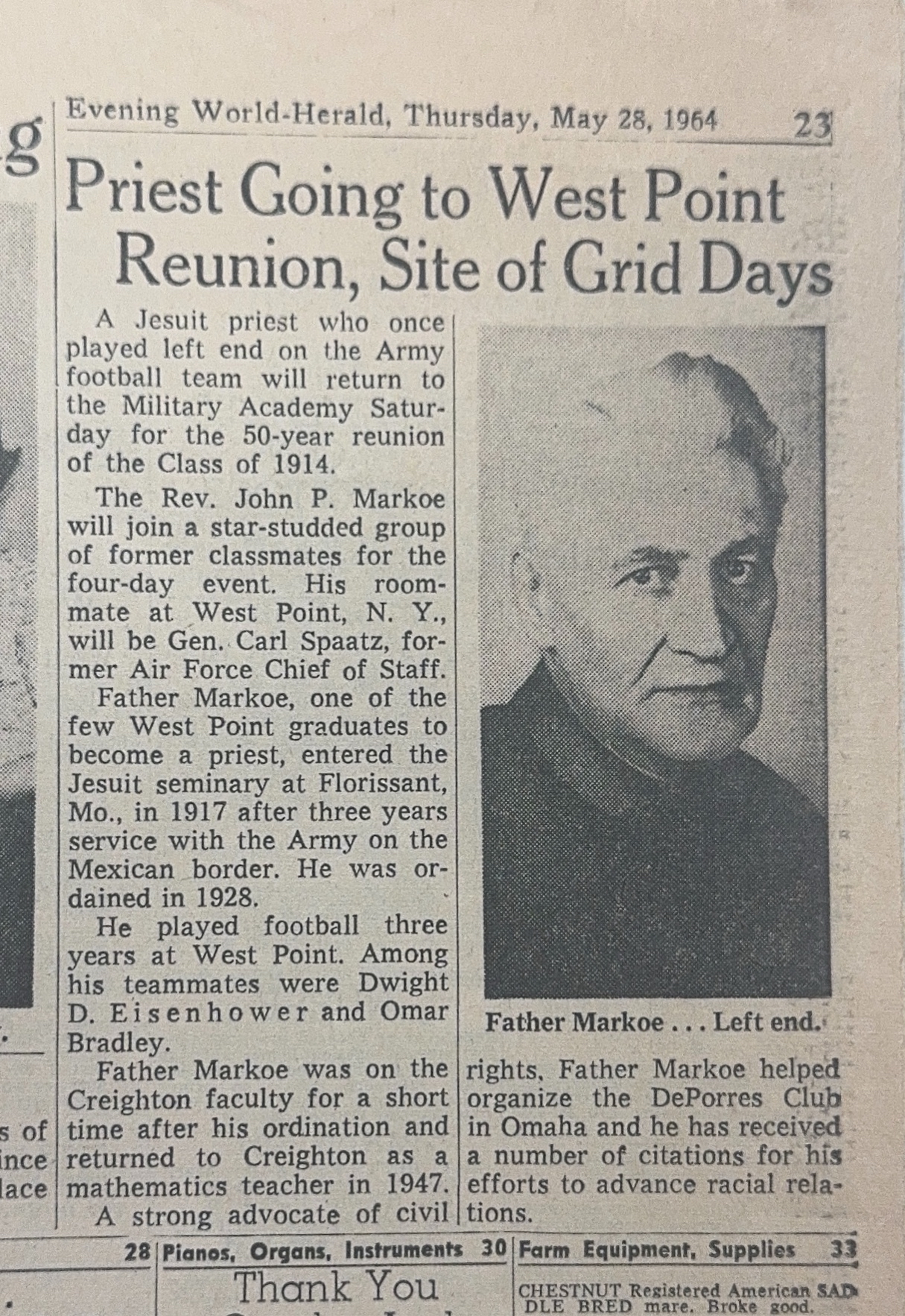

West Point Years (1910–1914): In 1910, Markoe entered the United States Military Academy at West Point, one of the country’s most prestigious military institutions. There, he trained alongside classmates who would shape American history, including future President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who was one year behind him.

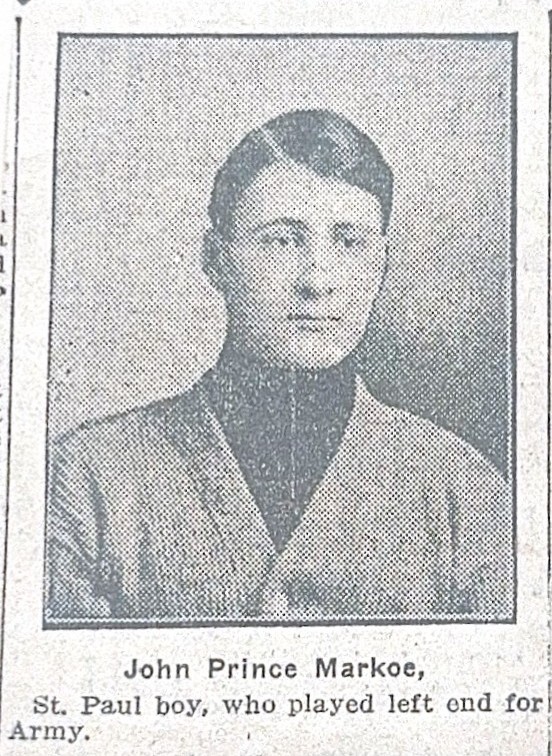

Markoe’s talents weren’t limited to the classroom. He quickly gained recognition on the football field, playing left end for the West Point team and earning selection to the All-American team multiple times.

In spite of his success, talents, and popularity, Markoe fought a personal battle with alcohol. His heavy drinking attracted the concern of both classmates and superiors. At one point, his continued enrollment at West Point was placed under strict conditions: Major General Thomas H. Barry issued a formal warning that Markoe’s next alcohol infraction would result in expulsion. His fellow cadets agreed to help watch over him, with the understanding that if John slipped again, they were obligated to report him. Markoe graduated on June 1, 1914, and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army.

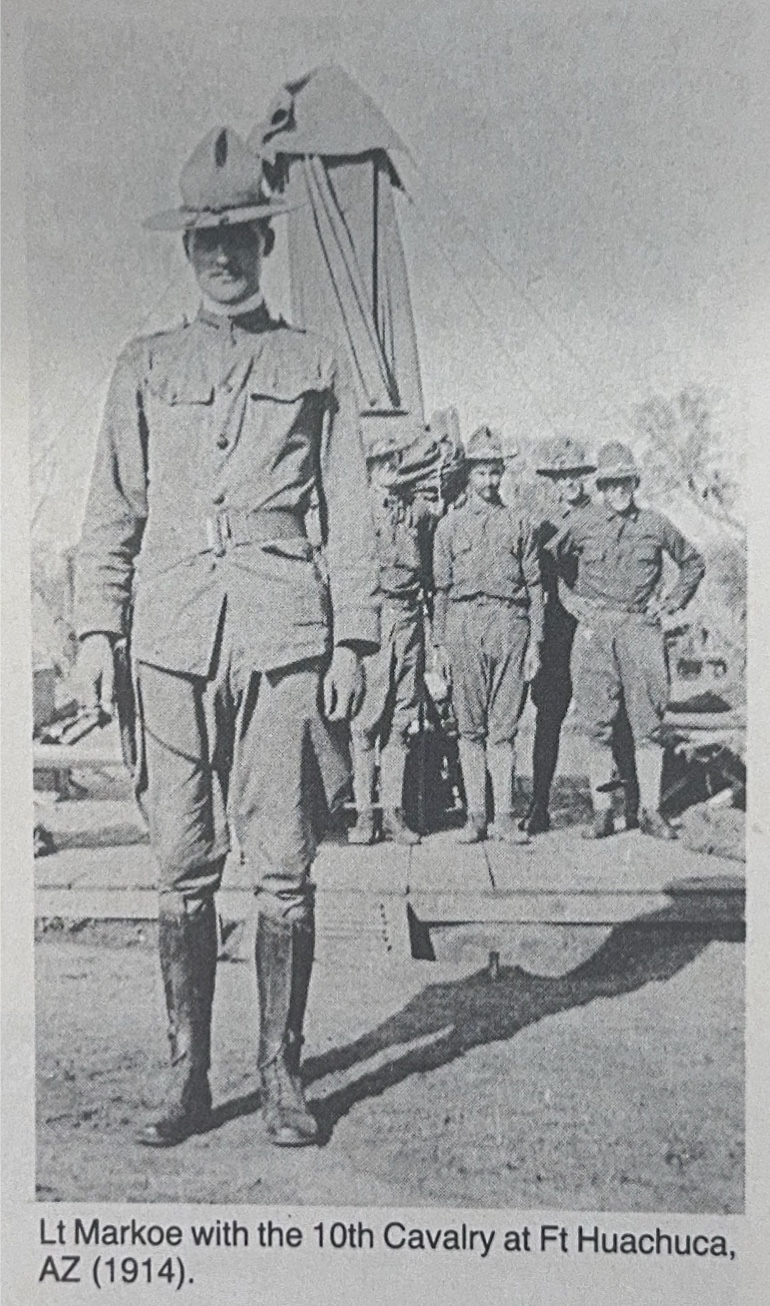

Military Service and Dismissal (1914–1915): Markoe was assigned to the Tenth Cavalry Regiment. Stationed at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, his role as a white officer leading Black troops left a deep and lasting impression on him. He often spoke later in life about the respect and camaraderie he shared with his fellow soldiers — and about the sharp injustice he felt when they were forced to part ways in segregated American towns.

In 1915, while stationed along the Mexican border near Naco, Arizona, Markoe’s struggle with alcohol resurfaced. A drinking-related incident ultimately led to formal charges of “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman.” His dismissal from the Army was finalized on March 10, 1915.

A Time of Drift: Life After the Army (1915–1916): Returning home to Minnesota, Markoe’s worked first as a lumberjack and helped build a dam across the Mississippi River before finding employment at the Minneapolis Steel and Machinery Company, where he produced ammunition for the British and Japanese militaries.

During this time, Markoe’s love for the military remained intact despite his dismissal. In 1916, he enlisted in the Minnesota National Guard as a private. He then served on the Mexican border as part of the Second Minnesota Infantry during the Punitive Expedition against Pancho Villa. After his unit was released from duty at Fort Snelling, he returned to civilian life.

While his official titles changed over time, one theme remained constant: his commitment to racial justice, shaped by the brotherhood he had shared with Black soldiers during his time in the Tenth Cavalry.

In later interviews, friends and acquaintances remembered Markoe as someone who never forgot the lessons of his military service. One acquaintance, Bertha. Calloway, recounted his stories of the deep divide between the solidarity experienced in the Army and the racial segregation encountered in civilian life. “He also told how whites and Blacks were supposed to go their ways separately when they went into town,” she said. “He didn’t like that.”

Markoe's affection for the ideals of military life endured throughout his life. His bond with his West Point classmates remained strong, and he made it a point to attend his class reunions for many years. These gatherings reflected the enduring respect he held for the values of camaraderie, discipline, and service that had first shaped his youth — values he carried into his Jesuit mission for justice.