National

Papal Encyclicals

The Secret Encyclical

In 1938, Pope Piux XI requested that John LaFarge, SJ draft an encyclical "that he could deliver to the universal Church, demonstrating the incompatability of Catholicism and racism" (Coppa, 1998). With the help of two other Jesuits – Gustav Gundlach, SJ of Germany and Gustave Desbuquois, SJ of France – La Farge wrote Humani Generis Unitas or "The Unity of the Human Race." The authors were sworn to secrecy until the encyclical's publication. The draft encyclical "argued that because of the existence of one natural law and one Creator, the human race is also one" (Chamedes, 2013). The document decred racisim and combatted antisemitism but it was still "tinged with a variety of Catholic anti-Judaism that had for centuries been an accepted doctrinal view" (Chamedes, 2013). The draft reached Pope Pius XI on January 21, 1939 (Chamedes, 2013).

Unfortunately, Pope Pius XI died less than a month later on February 10, 1939. The encyclical was discovered on his desk (Coppa, 1998). His former secretary of state and successor, Pope Pius XII, made the regrettable decision to shelve the encyclical. He "lacked the fighting spirit of his predecessor," and "preferred diplomacy to confrontation" (Coppa, 1998). Worred that the encyclical would "antagonize the Nazi regime," Pope Pius XII prioritized impoving relations with the German government over condemning racism and antisemitism (Coppa, 1998). At the end of his life, LaFarge broke the seal of secrecy and told a small number of his fellow Jesuits about the encyclical's existence. The story was revealed to the public in the late 1960s (Chamedes, 2013).

Mystici Corporis Christi

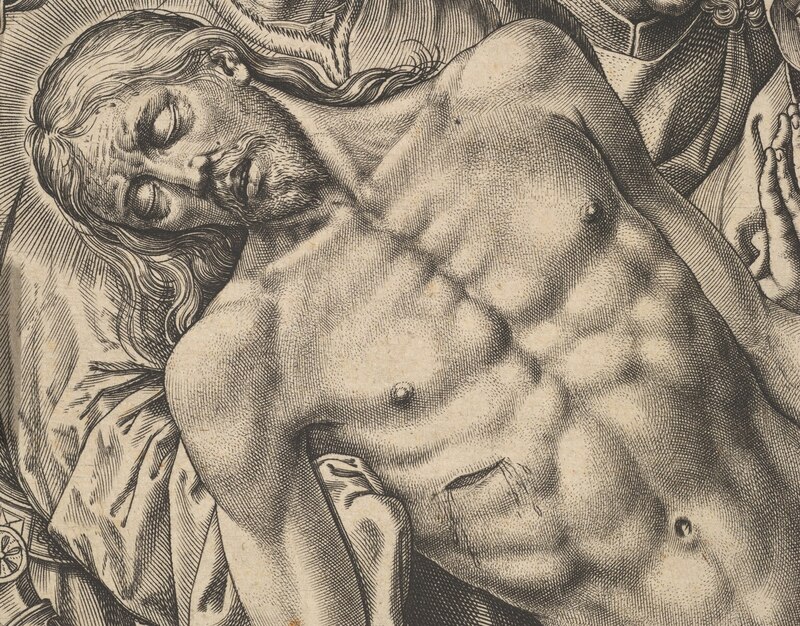

Mystici Corporis Christi is an encyclical of Pope Pius XII published in 1943. The encyclical illuminates the doctrine of understanding the Catholic Church as the Mystical Body of Christ and classifies all members of the Church as integral members of that body. The encyclical states, “But a body calls also for a multiplicity of members, which are linked together in such a way as to help one another. And as in the body when one member suffers, all the other members share its pain, and the healthy members come to the assistance of the ailing, so in the Church the individual members do not live for themselves alone, but also help their fellows, and all work in mutual collaboration for the common comfort and for the more perfect building of the whole Body” (Mystici Corporis Christi p. 15). This unitary understanding of the Church encouraged Catholics to fight to alleviate the sufferings of others. In the Civil Rights Movement, the Mystical Body doctrine provided justification for Christian involvement in righting the injustice faced by Black Americans. All Christians are members of the Body of Christ and thus have a responsibility to take action to redress the injustice faced by their brothers and sisters in Christ.

Catholic Civil Rights Organizations

Friendship House

Friendship House, founded in the 1930s by Catherine De Hueck Doherty, provided aid to the poor. The Friendship House was born of Doherty’s vocation from Christ to serve Him through immersion in poverty in the slums. Doherty took her prayer into action, founding the first Friendship House on September 14th, 1934, in Toronto. Sustained by prayer, Friendship House housed, educated, clothed, and fed the poor. Friendship Houses subsequently opened in Harlem, Chicago, Wisconsin, Washington D.C., Oregon, and Louisiana. As the operation grew, Catherine De Hueck Doherty became an advocate for social justice (Sharum, 1997).

Catholic Worker

The Catholic Worker Movement was founded by Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin in the midst of the Great Depression. They published the first issue of The Catholic Worker newspaper on May 1, 1933 and sold each copy for a penny. The paper was “for those who think that there is no hope for the future, no recognition of their plight” (History of the Catholic Worker Movement). Inspired by Catholic Social Teaching, the newspaper “discussed radical social change, support for workers, problems of industrialisation and the growth of cities. They suggested positive ways to tackle these things” (Dorothy Day). A grassroots movement arose from the ideals put forth by The Catholic Worker. Catholic Workers opened autonomous houses of hospitality and farming communes throughout the United States. The Catholic Worker lifestyle resembled that of religious orders, “With its stress on voluntary poverty, the Catholic Worker has much in common with the early Franciscans, while its accent on community, prayer and hospitality has Benedictine overtones” (Forest, 1997). But Dorothy Day did not create a blueprint for the Workers to follow. She simply lived her life and served her vocation in accordance with the Sermon on the Mount (The Life and Spirituality of Dorothy Day).

Through their indiscriminate ministry to the poor, Catholic Workers contended with racial discrimination. Shifting inner city demographics resulted in the mostly white Catholic Workers serving Black neighborhoods. “The Baltimore Catholic Worker, which was staffed by white workers, offered shelter to African Americans fleeing terrible conditions in the South” (Rice, 2019). The city deemed the integrated community a “public nuisance” and shut it down. Despite institutional intimidation, Catholic Workers did not shy away from interracial cooperation and justice. The Catholic Worker logo, designed by Ade Bethune, depicts a Black laborer shaking hands with a white laborer while Jesus embraces them both in his outstretched arms.

As a proponent of nonviolent protest – protesting for voting rights, labor rights, and an end to the military industrial complex – Dorothy Day was a natural ally for the Civil Rights Movement. She took several trips to the American South to document the conditions that Black Americans endured. One such trip took place in October 1956, just after the lynching of Emmett Till and during the Montgomery Bus Boycotts. Documenting low wages, inadequate education, and horrific violence against African Americans, she asserted that whites had ‘come to deny God in his brother, the Negro’” (Rice, 2019). She included her articles about this trip in her original manuscript for her 1963 book, Loaves and Fishes, highlight on an interracial farming commune she had visited. The chapter, entitled “The Negro and the Land of Cotton,” was “an interracial back-to-the- land venture that placed exceptional value on racial equality, the communal sharing of property, and dedication to pacifism” (Rice, 2019). The chapter was cut during the review process because it was considered too political.

Initially, Dorothy Day argued that Black liberation movements should focus on developing Black financial and societal infrastructure (Rice, 2019). However, as she learned more about Black American history and developed “a greater understanding of the pervasiveness of white superiority and prejudice,” Day lost confidence in any one solution to racism in the United States (Rice, 2019). But she continued to assert that “‘No one has a right to sit down and feel hopeless. There is too much work to do’” (Callaway, 2025). Inspired by St. Thérèse of Lisieux’s “little way,” Day stressed the importance of small acts of service. She recognized that the weight of rectifying institutionalized injustices could easily overwhelm even the most enthusiastic volunteers. So, in much the same way that Civil Rights organizations fought for change on a local level, she taught Catholic Workers to focus on the small acts of kindness and charity that they could accomplish in their day to day lives.

Statements by the Catholic Bishops of the United States

Discrimination of Christian Conscience

On November 14th, 1958, the Catholic Bishops of the United States came out with an official statement on the discrimination Black Americans faced throughout the United States. The document came late and long after individual Catholics and Catholic groups began to fight racial injustice, indicating how the Catholic Church delayed in officially joining the Civil Rights conversation. It urged American Catholics to act as an “obligation of justice” against racial injustice. Although the statement endorsed action, it warned against haste, communicating a lackluster message that did not activate American Catholics into action.

“It is a sign of wisdom, rather than weakness, to study carefully the problems we face, to prepare for advances, and to by-pass the nonessential if it interferes with essential progress.”

Statement on National Race Crisis

On April 25, 1968, the Catholic Bishops of the United States followed up on their 1958 statement, admitting they had not taken enough action against racial injustice. The document urged that the need for action was immediate and pressing, providing specific examples for actions to take for housing, education, and job opportunities as well as collaboration among other religious groups.

“There is no place for complacency and inertia. The hour is late and the need is critical. Let us act while there is still time for collaborative peaceful solutions.”

Vatican II

The Second Vatican Council spanned from 1962-1965. Throughout the council, the Church released numerous documents applying and clarifying Catholic doctrine in light of modern developments and needs. Vatican II empowered the laity to take a more active role in the Church. For example, one conciliar document states, “Since the laity, in accordance with their state of life, live in the midst of the world and its concerns, they are called by God to exercise their apostolate in the world like leaven, with the ardor of the spirit of Christ” (Apostolicam Actuositatem p. 2). Additionally, the Council prioritized ecumenical cooperation (Unitatis Redintegratio). Commission of the laity and greater cooperation with the greater Christian community outside of the Catholic Church provided further fuel for Catholics to engage in the fight for Civil Rights.