Religious & Theological Environment

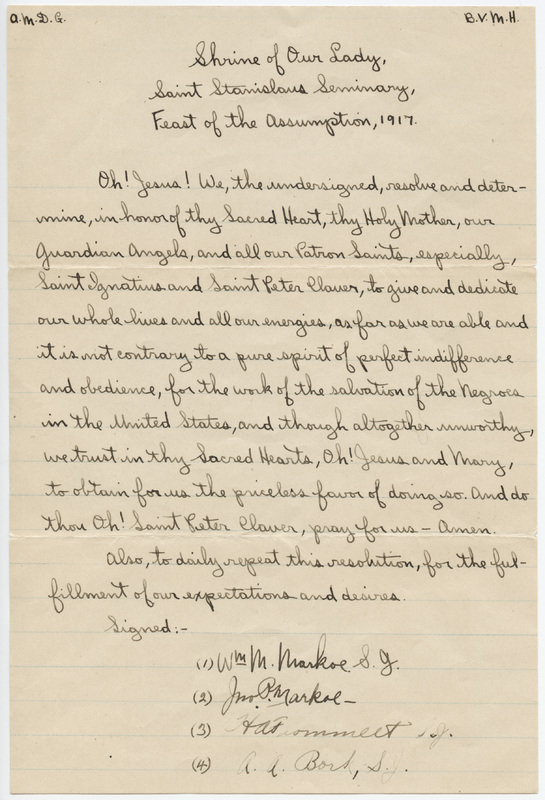

August 15, 1917: John Markoe gathered with his brother, William, and two other Jesuit novices in the Shrine of Our Lady located at St. Stanislaus Seminary in Florissant, MO. Taking turns, they each signed their name to the above pledge, dedicating their lives to the salvation of Black Americans.

“We, the undersigned, resolve and determine . . . to give and dedicate our whole lives and all our energies, as far as we are able and it is not contrary to a pure spirit of perfect indifference and obedience, for the work of the salvation of the Negroes in the United States” (Markoe Papers, B2 F5).

These four men voluntarily ministered to the Black communities in the St. Louis area, but they were not content just doing the work. They wanted to solidify their commitment in a formal ritual. Although these young Jesuits did not view this auxiliary vow as inconsistent with their Jesuit vows, it did cause friction throughout their priestly careers. Obedience to their superiors sometimes contradicted their devotion to the pursuit of racial justice. Through daily recitation of the 1917 pledge, they remained resolute.

St. Louis: A Transformative Environment

St. Louis and the surrounding area played an integral role in John Markoe’s discernment of his ministry to Black Americans. Markoe’s Minnesota childhood had not prepared him for the harsh realities of racism and white supremacy in Missouri. He did not have to look far to see those realities. As Markoe looked out the seminary windows in 1917, he could see the descendants of slaves who had worked on the seminary grounds living in shanties. In fact, given the year, it was possible that some of those people were actually men and women who had been enslaved by the Jesuits. Black Americans, free and enslaved, in the Florissant Valley area fostered a close-knit community. Thus, following emancipation, many of these people opted to stay in the area (Schmidt, 2021).

John joined his brother, William, in ministering to impoverished Black communities along the Missouri and Mississippi River bottoms. They visited shanty towns including Anglum and Sandtown (Holland, 2021). This was where the Markoe brothers began to see racism as a sin. They also began to recognize the hypocrisy in converting Black Americans to a segregated Church. The Markoe brothers turned their focus inward and resolved to rid the Church of racial discrimination (Holland, 2014).

DePorres Club Values

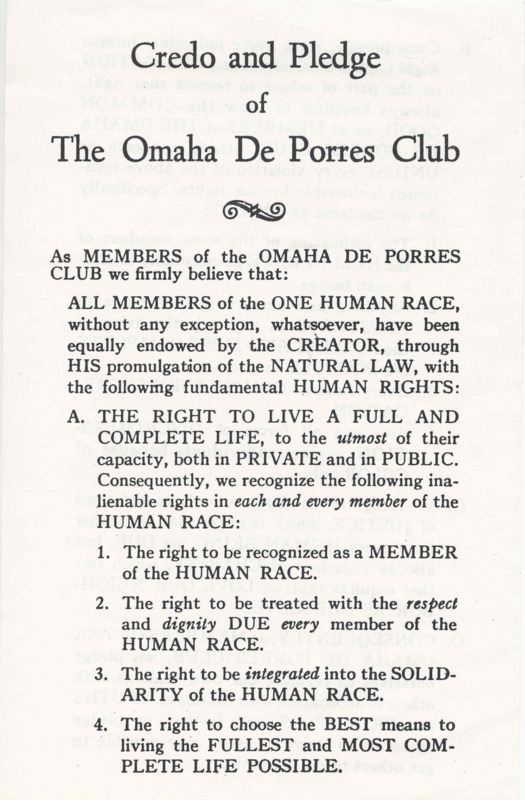

Fr. Markoe brought the values that his time in St. Louis had instilled in him to Creighton University in Omaha, NE. In the fall of 1947, he met with a group of college students who were interested in the intersection of morality and racism (Holland, 2014). That gathering gave birth to the Omaha DePorres Club. The club’s namesake spoke to their mission. St. Martin DePorres, of Spanish and African descent, was born in 1579. As a Dominican monk, he ministered to the poor of Lima, Peru, and demonstrated a special concern for the area’s African slaves (Holland, 2014). The club sought his patronage because of his dedication to racial harmony and social justice.

“The stated purpose of the club was ‘to educate people to think along the lines of charity and justice as regards inter-racial matters’” (Holland, 2014). The club’s Catholic origins steered its early efforts toward the integration of Catholic institutions (Holland, 2014). The immorality of racism and segregation was clear to the members of the DePorres Club, but the task of facing Church leaders head-on was daunting. Virginia Walsh expressed the mixed feelings that accompanied the club’s work: “‘It was such an amazing idea to think that we could do something about changing it. It just takes your breath away. It was just wonderful, but scary. Very scary. I was afraid the whole time’” (Holland, 2014).

The DePorres Club minutes reflect Fr. Markoe’s habit of constantly reminding the members that they had morality on their side. In the midst of mundane meeting procedures lie incredible gems of wisdom uttered by Fr. Markoe. For example, the February 9, 1948 meeting concluded with the following thoughts: “(1) Segregation is the modern heresy within Christianity — it is the work of the devil; (2) Society is the sinner and (3) The social pattern of ignorance results in segregation” (Markoe Papers, B7 F5).

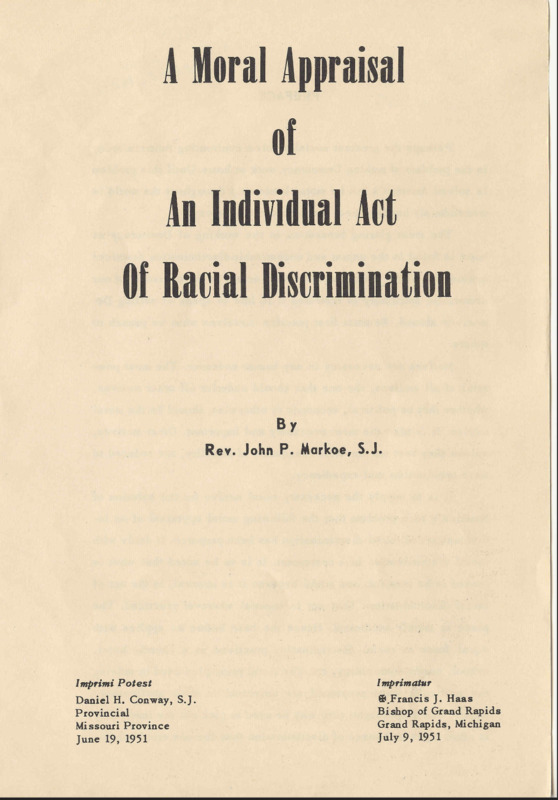

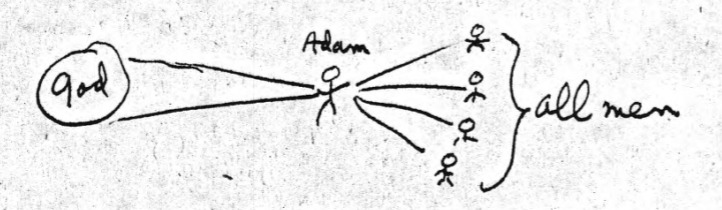

The foundation of Fr. Markoe’s denouncement of racism was not difficult for his disciples to follow. “There was never much of the intellectual about him. His concepts were disarmingly naive, straightforward and inevitably right” (Markoe Papers, B4 F25). Utilizing his mathematical approach to the world, Fr. Markoe created a proof outlining his moral objections to racism and segregation. The resulting argument, “A Moral Appraisal of the Color Line” was presented as a speech and published in the August 1948 copy of The Holmiletic and Pastoral Review. In it, Fr. Markoe concluded, “Our final appraisal of this pernicious social custom is, to use mathematical language, that the Color Line is immoral to the third degree” (Markoe Papers, B4 F12). At the first meeting, DePorres club members were instructed by listening to a recording of this speech.

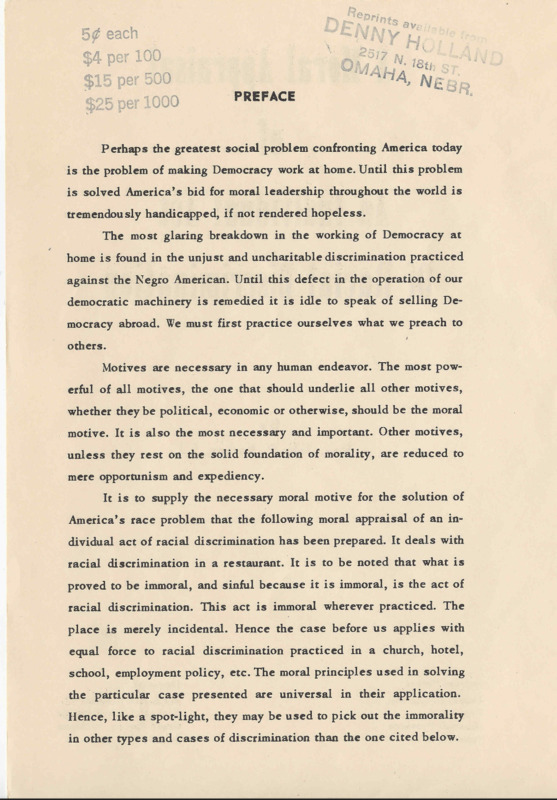

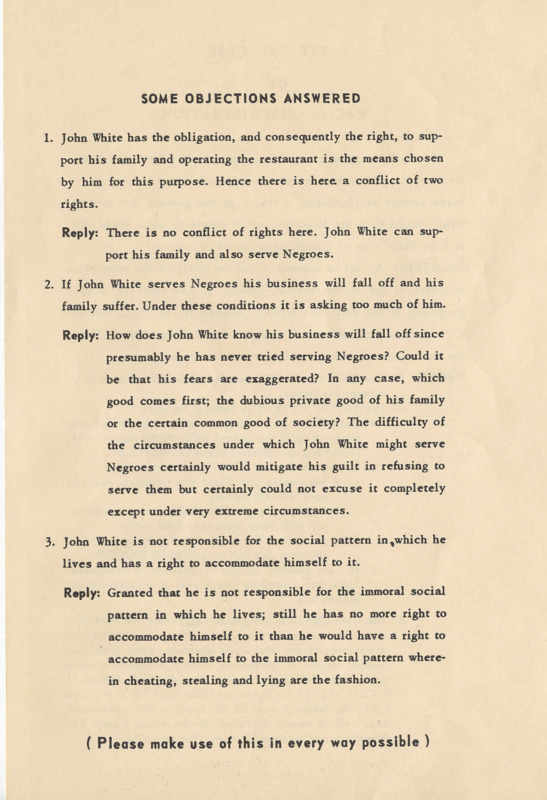

The DePorres club simplified Fr. Markoe’s proof and published a pamphlet for wide distribution. The document began with an appeal to American exceptionalism, arguing that America could not effectively promote democracy on a worldwide scale while it continued to infringe on the rights of its own citizens.

“The most glaring breakdown in the working of Democracy at home is found in the unjust and uncharitable discrimination practiced against the Negro American. Until this defect in the operation of our democratic machinery is remedied it is idle to speak of selling Democracy abroad. We must first practice ourselves what we preach to others” (Markoe Papers, B4 F3).

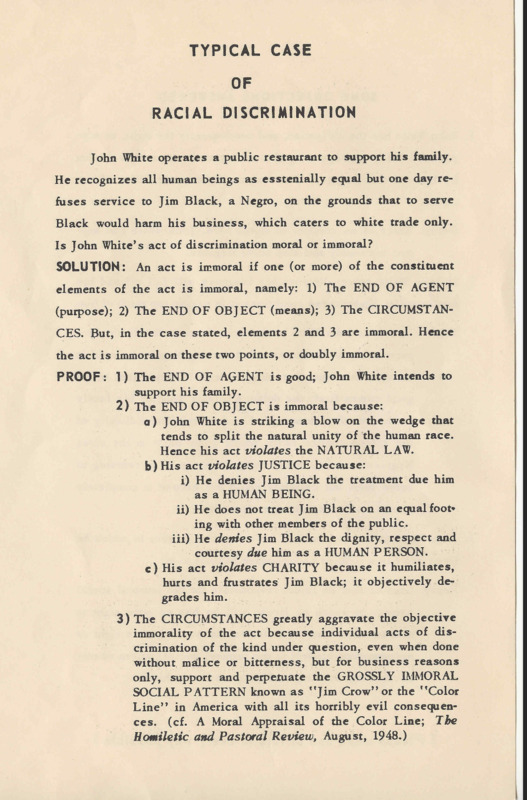

“A Moral Appraisal of an Individual Act of Racism” invoked natural law and charity to explain the immorality of a restaurant owner refusing to serve a Black man. Through this one example, the pamphlet proved the immorality of racism in all its forms. “It is to be noted that what is proved to be immoral, and sinful because it is immoral, is the act of racial discrimination. This act is immoral wherever practiced. The place is merely incidental” (Markoe Papers, B4 F3).

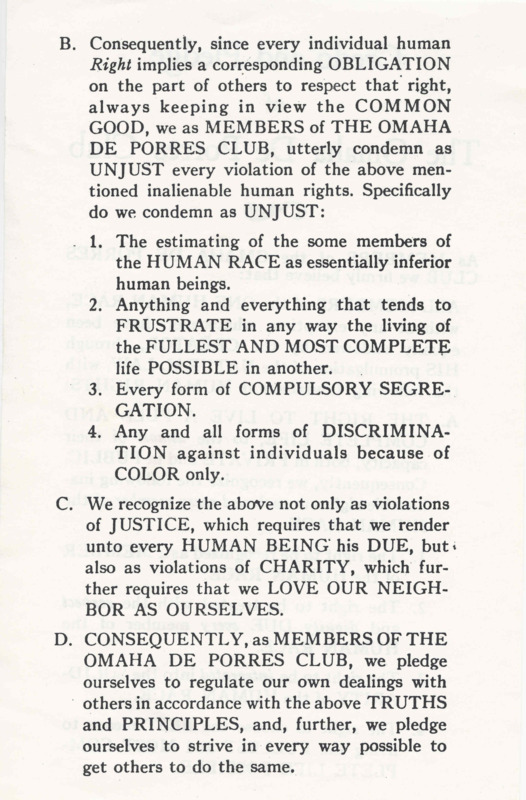

At the November 24, 1947 meeting of the DePorres Club, Fr. Markoe “briefly outlined on the blackboard the fundamental unity of the human race, the basic inalienable rights flowing from that unity, and emphasized that the whole matter was one of justice and as such became a moral problem” (Markoe Papers B7 F5). This outline informed the “Credo and Pledge of the Omaha DePorres Club.” With a foundation in natural law, this document set forth the club’s core beliefs, however, some of the more specific economic and social rights that Fr. Markoe originally outline did not make the cut. Markoe’s outline was as follows:

“From the fact that we all come from the same Creator and descend from the same ancestor Adam, and have the same human nature — come certain rights belonging to and following from that human nature. Some of these are:

- Right to fullest life possible;

- living wage

- right to own private property;

- choose partner;

- be accorded the decent human respect and dignity belonging to a man;

- be considered a member of the human race” (Markoe Papers B7 F5).

Though the DePorres Club advocated for fair employment and fair housing through their boycotts and other forms of direct action, they did not include points 2-4 in their credo. Perhaps their more specific aims did not make the credo in an effort to emphasize the right to a full life in all ways. But it is possible that the club opted to keep its credo more abstract so that people did not immediately reject the entire argument.

The Omaha DePorres Club was considered a radical group within the Catholic Church. There were other organizations working toward interracial justice at the time, but the cause did not become mainstream among American Catholics until the 1960s.